President James A. Garfield lived for 10 weeks after being shot in a Washington, D.C., railway station on July 2, 1881.

Alexander Graham Bell—best known as the inventor of the telephone—rushed to develop an electromagnetic device that could locate a bullet lodged in the president’s body. Brought to Garfield’s bedside, the forerunner of today’s metal detector failed for reasons that were not immediately clear.

The president died on September 16; his assassin was hanged a year later.

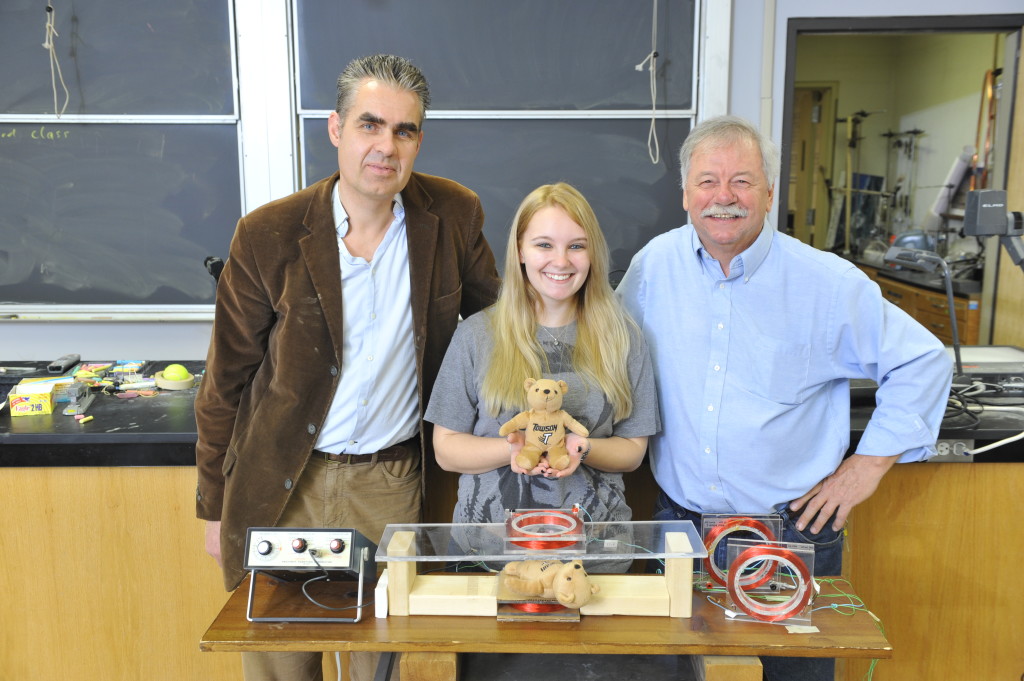

That dramatic confluence of science and history inspired James Overduin, assistant professor of physics, to create a simple-but-dramatic classroom demonstration with help from Dana Molloy, then an undergraduate physics major, and Jim Selway, a veteran high-school physics teacher. Their article, “Physics Almost Saved the President! Electromagnetic Induction and the Assassination of James Garfield: A Teaching Opportunity in Introductory Physics,” appeared in the March 2014 issue of The Physics Teacher.

Then things got interesting, said Overduin.

Nutopia Productions, which was producing “My Million Dollar Invention” for the Smithsonian Channel, asked to film the TU demo for the series’ “Life and Death” episode.

The TU demo involved a simple metal detector similar to Bell’s 1881 model, though it used a small speaker instead of a telephone receiver. When the Nutopia crew came to campus in May 2014, Overduin, Molloy and Selway substituted a medical dummy for the identical teddy bears—one with a concealed “bullet”—that they’d used in earlier versions.

“We filmed in a room in the Media Center basement,” said Molloy, now a teacher in Rye, New York. “Dr. Overduin explained the inspiration for the demo and how we replicated Bell’s metal detector.”

Molloy then took over as the storyteller: locating a bullet in the dummy’s chest cavity while explaining the concept of induction balance—all in the context of a national tragedy involving a gravely wounded president and a famous inventor’s race to save his life.

Professor Overduin says students are almost always baffled by Bell’s failure, which can be explained by another invention that debuted in the late 1800s: the innerspring mattress. Bell knew that any reactive metal on or near the wounded president would adversely affect his device. He didn’t know then that his patient was lying atop steel coils.

Ironically, Garfield died from infection caused by his doctors’ unsanitary practices, not from bullet-inflicted damage. TU’s Overduin, Molloy and Selway show how this historic event—and the “what ifs” surrounding it—can still haunt, fascinate and educate.

The Smithsonian Channel’s “My Million Dollar Invention: Life and Death” premieres on July 19. See your local listings for times.